“We have a total of 30 rooms, and 29 of them are occupied by Chinese visitors here on inspection trips. Owner of the Hotel in Almaty told ShineGlobal.

The owner, originally from Fujian, China, came to Almaty alone after seeing the city’s business potential. He opened this hotel in September, primarily catering to Chinese guests.

“This isn’t even the peak season yet. When we first opened in September, rooms were fully booked several days in advance.” Hotel owner said.

This is one of the most tangible, ground-level signs of the growing wave of Chinese expansion into Central Asia. Macro-level data reflects the same trend. According to data from Tongcheng Travel, in the first 11 months of this year, the number of Chinese travelers to Kazakhstan exceeded 876,000 (compared with 655,000 for all of 2024). In addition, from early December through the New Year holiday period, flight bookings from major Chinese cities to Kazakhstan rose by more than 50% year-on-year, while hotel bookings surged by over 80%.

At this pace, the number of Chinese traveling to Kazakhstan this year could approach 1 million.

Beyond the movement of people, the flow of goods has also surged. From January to November, six major China’s railway ports operated a 13,089 China–Central Asia freight trains, shipping 1,031,695 TEUs of cargo—an increase of 30.6% year-on-year.

In addition to infrastructure, new energy, and 3C products leading trade growth, cross-border e-commerce has opened up new channels to the Central Asian market.

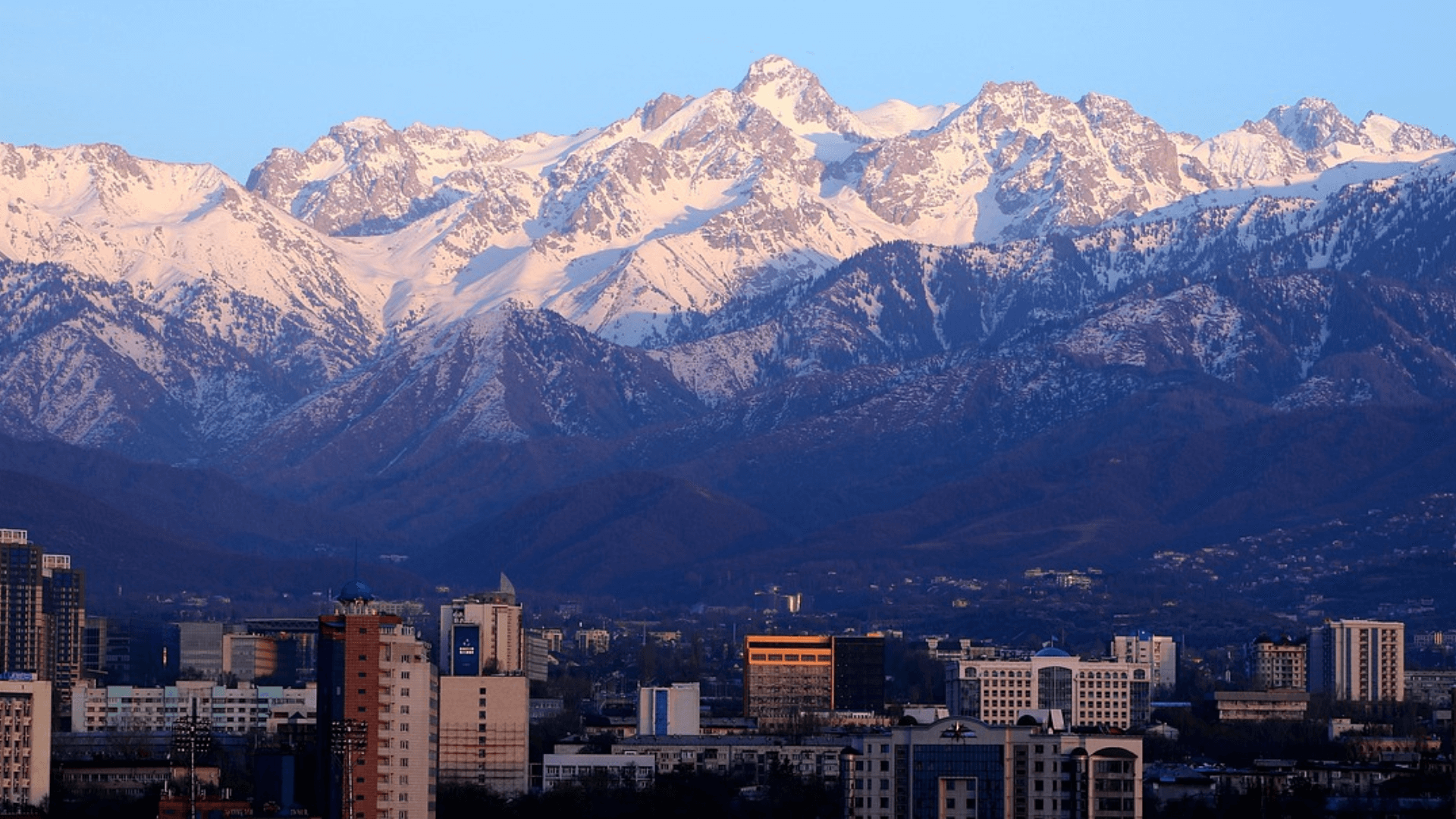

In mid-December, ShineGlobal conducted a five-day field study in Almaty, to gain deeper insight into this market in transition. One immediate impression was that while the city’s infrastructure resembles that of China’s second-tier cities from 10 to 15 years ago, its digitalization is advancing rapidly. E-commerce, ride-hailing apps, online entertainment, and online booking of hotels&homestays have become part of everyday life, with Chinese popular tea beverages and new energy vehicles increasingly visible on the streets. Meanwhile, the local economy is shifting from an “energy hinterland” to a “diversified cooperation zone,” with Chinese companies emerging as a new employment favorite among young people.

Looking ahead to 2025, this may well mark a historic turning point at which the Central Asian market enters a phase of comprehensive upgrading.

E-Commerce become everyday life between young generation

The “-stan” countries of Central Asia in many people’s minds, are lands of vast steppes and deserts, hospitable nomads, and rich culinary traditions.

When we come to this place, however, The atmosphere was more like a small Eastern European city—two weeks before Christmas in December, almost every shop along the streets in Almaty is decorated for the holiday; Russian-style architecture is the most common building here; traffic jams are constant, no matter the time of day—roads are clogged even at 11 a.m., and evening rush hour congestion is just a normal part of life.

4 p.m in the afternoon, Cars are waiting in the line on the Main Street in Almaty

Traffic jams can even help cultivate patience.

Life here moves at a more relaxed pace—commuting to work is done not just by taxi or bus, but more on foot. Even delivering takeout can be done by walking…

The local delivery person is walking to deliver the food. Locals hardly order because it’s inconvence.

In fact, for Chinese newcomers visiting here for the first time, there are usually a variety of guides teaching how to achieve a “seamless experience” through different apps: how to activate “Belt and Road” data plans, how to hail a ride with Yandex Go, how to pay via Kaspi QR (now linked with Alipay), how to check local buses using map apps, and how to shop online.

Kuma is a local senior in university, moved with her family from China to Kazakhstan in 2021 and is now interning at a Chinese automotive service company. She told ShineGlobal that when she first arrived in Almaty, e-commerce was still underdeveloped, and for someone already used to China’s mature online shopping environment, it was extremely inconvenient. But now, she shops online two to three times a week. “E-commerce here is not much different from China in terms of experience—the only difference is that there’s no free shipping.”

Today, Kazakhstan hosts not only local e-commerce platforms like Kaspi.kz, Russian platforms such as Wildberries (WB) and Ozon, but also Chinese cross-border platforms like Taobao, AliExpress, and Temu. Through Chinese platforms, users can purchase goods from China and have them shipped to Almaty and other cities via transit warehouses in Xi’an or Urumqi, making the shopping experience very effficient.

Overall, Kazakhstan owns the most developed e-commerce infrastructure in Central Asia. Internet penetration (92.9%) and mobile connectivity (128%) are the highest in the region, and online shopping habits are well established. E-commerce’s share of retail sales rose from 0.5% in 2013 to 14.1% in 2024. Over the past five years, Kazakhstan’s e-commerce market has grown sevenfold, reaching 3.156 trillion tenge (about $6.5 billion) in 2024, a 33% year-on-year increase.

Ma Jing, head of Yandex Ads Greater China, told ShineGlobal that e-commerce acts as both a “catalyst” and a “microcosm” of digital transformation, bringing three major changes:

- Inclusive consumption: It breaks down geographic limitations, allowing residents in small towns and rural areas nearly the same access to products as in big cities.

- New jobs and entrepreneurship: It drives demand for digital marketing, local e-commerce operations, warehousing and logistics, and customer service, while also spurring a wave of local small-business entrepreneurship.

- Commercial infrastructure upgrades: Payment systems, logistics, and trust mechanisms (like ratings and customer service) have rapidly matured under the push of e-commerce.

Take payments as an example: beyond online shopping and ride-hailing, some vendors in Almaty’s oldest and most famous marketplace, Green Bazaar, selling agricultural products and handmade goods, now accept Kaspi QR payments. This indicates that electronic payments are gradually spreading from online to offline spaces.

For Chinese companies, Kazakhstan is the easiest market in Central Asia to scale, the most suitable for warehouse and logistics setup, and likely the fastest to achieve a positive ROI.

Meanwhile, Uzbekistan, leveraging its massive population, has become the region’s most important e-commerce market. With an internet penetration rate of 89%, its overall digital infrastructure is rapidly improving. With a population of 37 million, it represents Central Asia’s largest potential consumer market. As local e-commerce platforms like Uzum, along with Chinese platforms such as AliExpress and Temu, gain traction, transaction volumes continue to grow at double-digit rates.

Another market is Kyrgyzstan. Its internet penetration is comparable to Uzbekistan’s. Although its overall economy is smaller, users rely heavily on online channels, e-commerce adoption is rapid, and categories such as apparel, small home appliances, and daily necessities are showing strong growth. For merchants who would like to build business in Central Asia, Kyrgyzstan is ideal as a low-cost test market: using platform entry and lightweight overseas warehouse models, businesses can observe user demand and iterate quickly.

Central Asia missed the early PC internet era but is now catching up with the mobile internet wave. About 95% of netizens access the internet via smartphones, and consumer decision-making heavily relies on mobile. ShineGlobal found that popular apps for ride-hailing, payments, online recruitment, and car purchases only started appearing or being promoted after 2020. Moreover, it is common here for a single app to integrate multiple functions. Take Yandex, for example—it combines search, mobility, food delivery, car rentals, etc., forming a “Super AppDigital ecosystem” .

Ma Jing explained that Yandex Kazakhstan is building a deeply integrated digital ecosystem, which has become a core part of the country’s online infrastructure. Each month, 10 million people use Yandex Kazakhstan’s services, and over 9 million searches are conducted daily on Yandex. The Yandex Advertising Network (YAN) has 45,000 partners, creating opportunities for brands to establish lasting engagement with local active consumers.

Data shows that in the first half of 2025, the number of Chinese advertisers using Yandex Ads in Kazakhstan grew 76% year-on-year, while ad spending surged 192%. The main growth driver comes from the industrial equipment and materials sector, whose ad investment accounted for 75% of Chinese companies’ total Yandex Ads spend in Kazakhstan—more than five times higher than the same period in 2024. The gaming industry was the fastest-growing category, with ad spending increasing nearly eightfold. IT services, logistics, and home goods sectors also saw strong double- and even triple-digit growth.

Yandex Office Building in Almaty

These figures indicate that Chinese companies are leveraging Yandex Ads’ localized performance marketing tools to align their competitive advantages precisely with Central Asian market demand, enabling rapid and large-scale expansion into new niche segments.

Ma Jing also noted that Central Asian consumers have historically been influenced by European products and tend to favor Western-style aesthetics. For businesses marketing here, a key principle is to “go beyond translation and achieve cultural resonance”—content should incorporate local holidays, trends, and internet slang, while channels must deeply engage with national-level local ecosystems rather than simply replicating domestic channel matrices.

From everyday life to commercial marketing, digitalization is comprehensively transforming this market.

02 From Bubble Tea to EVs, Chinese goods brought a consumption upgrad

Digital transformation is reshaping local lifestyles while new consumer trends are enhancing people’s quality of life.

In Almaty, the globally popular beverage chain Mixue Ice Cream & Tea has also arrived. Right next to Almaty train station, there’s a Mixue store, and beside it sits another new tea brand from Henan—WEDRINK (Cha Zhuzhang).

The Mixue in Almaty maintains a visual design very similar to its stores in China, and the range of drinks offered is largely the same. ShineGlobal observed that prices here are generally higher than in China. For example, a strawberry sundae costs 600 tenge (about 1.18USD) in Almaty, compared with roughly 0.86USD for the same item in China.

Though the difference is only 0.32USD, for a brand like Mixue, which emphasizes extreme cost-performance, this represents a higher price tier. However, for local consumers, this price is quite reasonable. After all, with average monthly salaries around 716– 859USD, daily consumer goods often cost nearly twice—or even more than—what they would in large cities in China.

Through conversations with store staff, ShineGlobal learned that Mixue entered the Central Asian market about a year ago and now has more than ten stores in Kazakhstan, as well as locations in Uzbekistan. The brand is still in the early stages of expansion.

By comparison, WEDRINK has been expanding even more aggressively in Kazakhstan, reportedly already operating over a hundred stores. According to WEDRINK’s official announcements, it has extended into Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan, Tajikistan, and Kyrgyzstan. Undoubtedly, WEDRINK’s market penetration here is far higher than Mixue’s.

Beyond New-style Tea, Chinese energy vehicles (EV’s) have also become a visible part of the cityscape. On the streets of Almaty, BYD, Hongqi, Li Auto, and Zeekr frequently stand out among traditional vehicles.

Because Kazakhstan does nothave a Scrapping age limit, with fuel prices relatively low (around 0.4–0.6 USD per liter), the streets are filled with traditional oil cars. Volzhas Kuspekov, a member of the Mazhilis (the lower house of parliament), revealed in an interview with the program Бүгін LIVE that there are over 5 million registered passenger cars in Kazakhstan, nearly 80% of which are more than 10 years old.

Mr. Xing, the head of an automotive service company operating in Kazakhstan, told ShineGlobal that the high number of oil cars has created strong demand for automotive services. With the arrival of Chinese car brands in recent years, many Chinese automakers have established after-sales service points, similar to 4S dealerships, in Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan, and other countries. His company, Wankao Auto, which has a Sino-European background in automotive warranty and cross-border trade services, has already set up operations for car repairs and warranties in Central Asia, including Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan.

Except repair, another shift is: to address the oversupply of old traditional cars, the Kazakh government plans to launch a “trade-in for new” program. Local media also reported that Kazakhstan will introduce a car leasing program limited to new vehicles, with the major highlight being no down payment required.

Perhaps as a result, demand for Chinese car brands in Kazakhstan surged in the first half of 2025. According to CAAM(China Association of Automobile Manufacturers), from January to June 2025, Kazakhstan imported approximately 77,600 Chinese cars—double the volume from the previous year—making it one of the top ten global import markets for Chinese vehicles.

Industry insiders have even noted that about 45% of Chinese cars shipped to Central Asia are sold in Kazakhstan. While automotive consumption in high-spending markets like Europe and the U.S. has slowed, the rapidly growing car market in Central Asia has become a “hot spot” for automakers.

To support the local EV’s market, Kazakhstan began planning a charging network in major cities in 2024, with projections that by 2030, more than 60% of the country will be covered by charging stations.

03 After being rejected for a long time, A new reflections on Chinese businessmen overseas.

The market may seem promising, but it’s not an easy for Chinese merchants.

A car trade worker who has been in the local market for a year, told ShineGlobal that Kazakh people tend to prefer purchasing cars from local dealers. “Chinese car dealers opening stores here hardly make sales. Even if you offer very low prices, locals are reluctant to buy—they’d rather pay more to buy from a local brand.”

This preference stems from the importance locals place on consistent after-sales service. In the past, some Chinese automakers faced after-sales disputes that left consumers with negative experiences, damaging Chinese automakers’ reputation.

At the same time, after-sales expectations can be extremely demanding. For example, locals sometimes require that repaired engines or gearboxes perform like new. “I once had a customer who insisted that a repaired vehicle’s performance must be identical to a new car. We explained that a repaired vehicle could never be completely like new, but he refused to accept it. Eventually, we even had to call the police to mediate.”

This illustrates that while opportunities are significant, entering the Kazakh automotive market requires careful attention to after-sales service, reputation management, and the high expectations of local consumers.

Chinese EV in Almaty

Kimi, founder of Hami Information, began entering the Kazakh market in 2022. Having previously operated China-to-Europe cross-border logistics, she was familiar with customs, border procedures, and local fleet resources. Yet, she faced a major setback at the start: she hired a local partner to manage project promotion in Kazakhstan, After sometime Kimi discovered that the partner had packaged the company’s resources and app project as his own, seeking external investment and selling it. When the scheme was uncovered, it led to legal disputes, causing trouble both for the partner and for Kimi’s company.

“In Central Asia, if you want to do business but don’t want to be hands-on and rely solely on financial investment, you’re very likely to fall into a trap. You have to personally investigate, pay close attention, and be cautious. Decisions need to be made slowly—there’s no other way,” Kimi said.

In reality, Central Asian countries are currently in a transitional period of economic reform, social opening, and policy adjustment. The local social norms, industrial policies, and enforcement practices all require extra vigilance from foreign investors.

Currently, global attention is concentrating on Central Asia. In addition to the annual Central Asia Summit between China and the five Central Asian countries, the U.S., EU, Japan, and other economic powers have also held C5+1 summits with the region this year, seeking various forms of cooperation. This strategically important, resource-rich market is increasingly taking control of its own agenda.

For companies aiming to integrate deeply into this market, it is crucial to align their capital and technological advantages with Kazakhstan’s national transformation strategies and the concrete interests of local partners. Instead of simply exporting finished products, exploring local assembly or partial component manufacturing can generate significant employment opportunities. Rather than sending Chinese staff abroad, hiring and cultivating trustworthy local talent can also ease internal conflicts caused by cultural and work habit differences.

A recent development we found that while hotel and service jobs were once the most common post-graduation choices, Chinese companies in Kazakhstan have now become one of the most sought-after employers among young locals in converwsations with local College students.