Recently, Chinese e-commerce giant Shein opened its first-ever global store at the BHV department store in Paris, sparking a huge uproar.

Since the announcement of the store in October 2025, Shein has quickly become the focus of public debate in France. The media has continuously published critical reports, various brands and organizations have launched joint protests, petitions, and street demonstrations, and government authorities have repeatedly raised concerns. Over the course of several weeks of controversy, Shein’s store-opening plans have been scrutinized under a microscope: officials have issued frequent statements, influencers have voiced their opinions one after another, and many even predicted that BHV would abandon the cooperation under pressure.

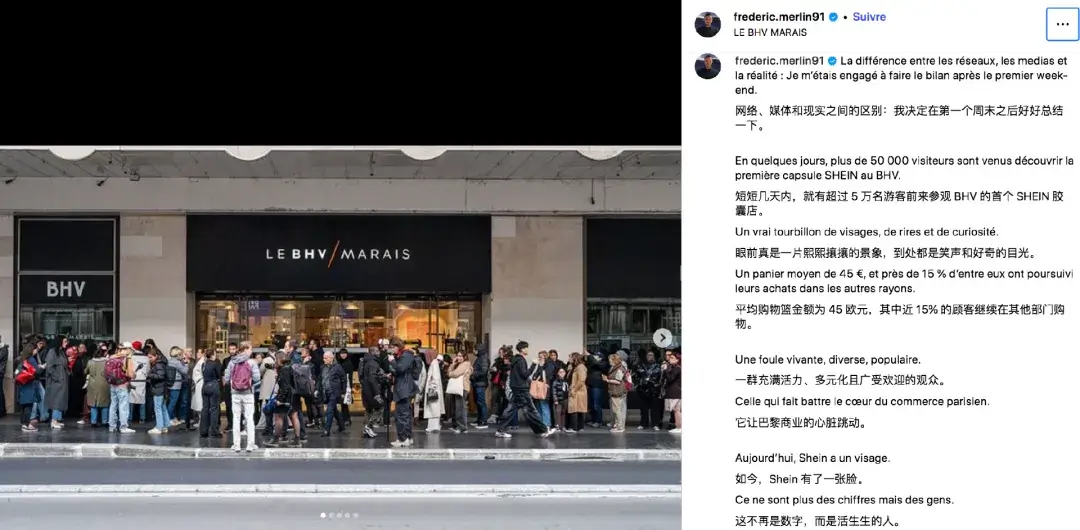

On Wednesday, November 5th, despite enormous pressure, Shein’s first permanent offline store worldwide opened as scheduled at BHV. The day was full of French-style irony: angry protesters on the left, customers lined up around corners on the right, and heavily armed police in between; protesters were nearly infuriated by the endless stream of shoppers, and with the media fanning the flames, the two sides almost clashed; the customers at the front briefly enjoyed celebrity-like treatment, surrounded by cameras and photographers, appearing on the front pages of major media outlets.

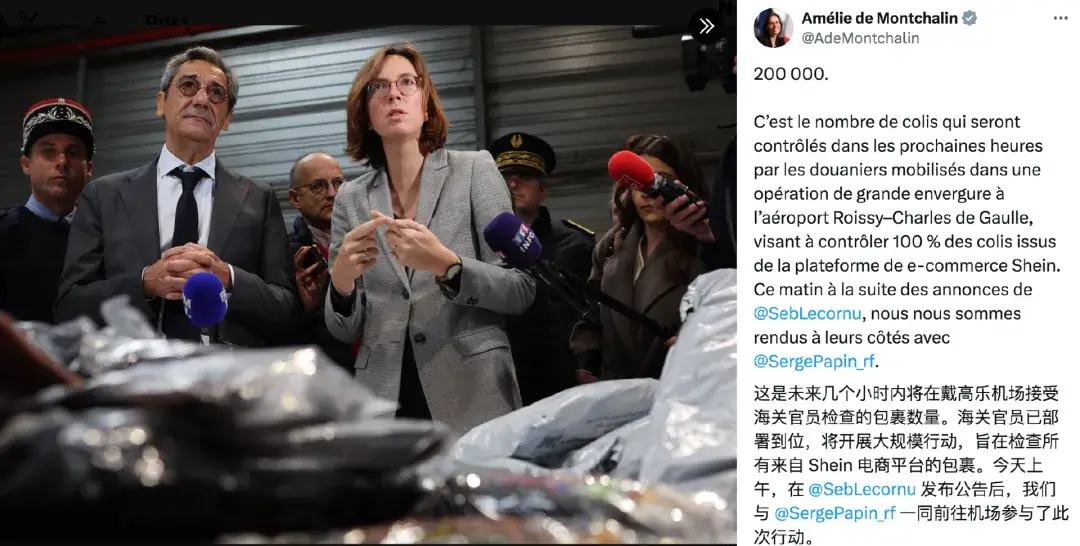

This time, France seemed ready to take serious action. That evening, French Prime Minister announced the official launch of a ban on Shein and intercepted all Shein packages arriving in France within 24 hours, opening each one for inspection.

The situation escalated quickly.

What should have been a celebratory occasion was instead threatened with a possible ban, with consequences far beyond anyone’s expectations. As a writer living in France and closely observing cross-border e-commerce for years, I consulted a large amount of information and conducted field visits, trying to understand some fundamental questions:

Who are the buyers?

Who are the opponents?

And what are the deeper reasons behind all of this?

01 At the store, a vivid tableau of people in front of the shelves

BHV, located in the fashionable Marais district, boasts a history of 169 years and has long been a symbol of the lifestyle and aesthetic tastes of Paris’s middle class. Fashion-savvy visitors are certainly familiar with the Marais, a neighborhood that gathers the most distinctive concept stores, independent designer shops, vintage clothing stores, and boutique bars, firmly perched at the top of the fashion hierarchy.

The department store sits at the exit of the Hôtel de Ville metro station on Line 1, directly facing Paris City Hall, truly in the heart of the city. Today, stepping out of the metro, passersby are immediately confronted by the big advertisements of Shein & BHV. Their high-profile presence boldly signals Shein’s ambitious intentions, prompting many pedestrians to stop and take photos.

Poster at the main entrance of BHV features a photo of Frédéric Merlin, chairman of the French department store group, together with Shein CEO Tang Wei and his pet dog.

The caption reads, “We probably shouldn’t have made this poster,” a self-deprecating joke.

source: @RTL

On the 3rd day after the opening, during a weekday afternoon, the long queues had disappeared, but Shein was omnipresent: bold-font signs, repeated guidance stickers on the escalators, seemingly “pushing” visitors all the way up to the sixth floor. The higher you went, the denser the crowd became, and security personnel were noticeably more present, even a dedicated guard was stationed at the corner of the escalator from the fifth to the sixth floor. In the usually relaxed French department store security, this density stood out and subtly conveyed a rising tension.

Once on the sixth floor, the atmosphere changed immediately.

Long queue on opening day had vanished, but it was still crowded, bustling without being chaotic. Visitors spanned all ages, local French predominantly among with a few Chinese customers.It is hard to discrabe these onlookers or shoppers with any single stereotype. On the 6th floor, Peoples’ subtle differences, curiosity, hesitation, and natural judgment became visible(emerge?).

After standing there and Observing for a while, I found that there are a few different type of people :

“Meticulous Bargain Hunters”

Mostly are young women, intimately familiar with platform prices, and well-versed in cross-border shopping on Temu, Shein, and AliExpress. Their movements were swift, fingers deftly flipping price tags, eyes sharp as they scanned and compared with official websites. Muttering to themselves: “€25? That’s expensive, shouldn’t be this much,” “Without extra discounts, it’s cheaper online,” “This is cheaper on Temu.” Despite muttering, they ended up spending carefully but significantly.

“Practical Family Shoppers”

Middle-aged couples shopping for the whole family made up a large portion of visitors. Their eyes were fixed solely on value for money, focused entirely on daily necessities. For them, Shein was no different from any other affordable store: a convenient channel for careful household shopping.

“Trend Chasers”

This group matched the common perception of Shein’s target audience: arriving in packs.,It was less about shopping for them but more about chasing trends and accumulating social currency on Instagram or TikTok. They could name which designs referenced which brands, yet happily paid for them.

After all, trends are fleeting, and everything can be substituted.

“Affluent Millennials Experiencing Everyday Life”

Several young wealthy couples, clearly not short on money and carrying the latest Chanel hippie bags, came for the novelty experience of “checking out the ordinary.”

“Mouths Against, Hands For”

Some BHV’s traditional clientele came just for curiosity, yet many found the fun in treasure-hunting through “junk” items, exclaiming with delight: “This is actually pretty good, better than I expected.” Items averaging €20–30 were purchased for sheer enjoyment.

“The Virtue-Police”

One middle-aged local woman, visibly overweight, scanned the store with piercing eyes, randomly selecting a staff member and sternly asking: “Why are all the clothes only in small sizes? There isn’t a single piece I can wear. Is this grossophobia?” The young staff was flustered, mechanically repeated the rehearsed lines: “All items in the store, styles, quality, and prices are the same as online, so the sizes are the same as online…” Unable to get a satisfactory answer, the woman finally relented: “Don’t worry, I’m not singling you out.” The staffer exhaled in relief, murmuring in grievance, “It’s not my fault…”

Source@francebleu

Walking through the crowd, the word “prix” (price) was perhaps the most frequently mentioned.

Customers here had no expectations for Shein’s quality; they were simply looking for bargains and entertainment. It was this straightforward practicality that lent the scene an unexpectedly relaxed atmosphere.

Most of the clothing had a “third-tier Chinese county version of A-Lian” kind of French style—construction was close to street-market quality, and the price tags weren’t necessarily lower than people expected (without factoring in opening-day vouchers or stacked discounts). Yet in the French market, the cost-performance ratio remained its competitive edge.

As night fell, office workers began flowing in, and BHV’s evening truly began.

02 At the Heart of the Storm: Business, Media, and Politics

It was evident that the reality of in-person shopping did not match the media’s hype of a “nationwide boycott.” This stark disconnect reflects deeper fractures within French society, a silent clash of differing stances and social strata.

The strongest supporters were the “pro-China” business forces, represented by BHV.

The partnership between BHV and Shein is a classic case of resource exchange: BHV aims to leverage the foot traffic and data brought by Shein, particularly among younger customers; Shein, in turn, gains the century-old credibility of BHV and the opportunity for in-store try-ons to enhance its brand image, and even to touch on cultural discourse.

Frédéric Merlin, the owner of BHV’s parent company, clearly viewed the deal with satisfaction. He proudly posted the results on Instagram—by the fifth day after opening, the store had already attracted 50,000 visitors. Facing external criticism, he remained resolute: in the business world, stagnation equals decline, and BHV needs vitality and diversity, not inertia. He even countered brands, politicians, and commentators who criticized Shein, arguing that they were simply using the controversy to showcase themselves. Attacking Shein, he said, was a slight against the real consumers.

Instagram Post de Frédéric Merlin

Does he really care?

A telling moment was captured in a video on opening day: when protesters shouted at the queue, “Aren’t you ashamed?” the BHV owner leaned forward and kindly reassured the crowd: “Those who are screaming, they simply don’t care about people like you… people who don’t know how to dress.” (Tout ce qui hurle, ce sont ceux qui n’en n’ont rien à faire, des gens comme vous, qu’ils savent pas habiller.)

I believe he wasn’t intentionally mocking anyone—he was likely still adjusting his mindset. As the first in France to “take the leap,” the real reason he went against the grain to partner with Shein probably isn’t as lofty as the official rhetoric suggests. According to news reports, the storied department store has faced declining foot traffic for years and even owed suppliers for extended periods—hardly able to maintain the pride of being a “Parisian department store.” In this partnership, Shein is actually in the dominant position; for Shein, opening here is a bonus, but for BHV, it is almost a lifeline. BHV inevitably harbors complex feelings: it’s like a once-overlooked rural relative suddenly inheriting property—you need them, yet still want to profit with dignity.

There’s still much for him to learn from predecessors like LVMH. Luxury brands rely on the Chinese market while maintaining their European heritage; striking that balance is an art.

As for some BHV tenants withdrawing, such as APC, a brand familiar to Chinese consumers, although officially cited as a “values conflict,” the underlying reason remains rational business logic. These mid-to-high-end brands, traditionally aligned with BHV’s image of Parisian middle-class design sensibility, would see their carefully constructed storytelling undermined by sharing space with Shein, ultimately threatening their pricing power.

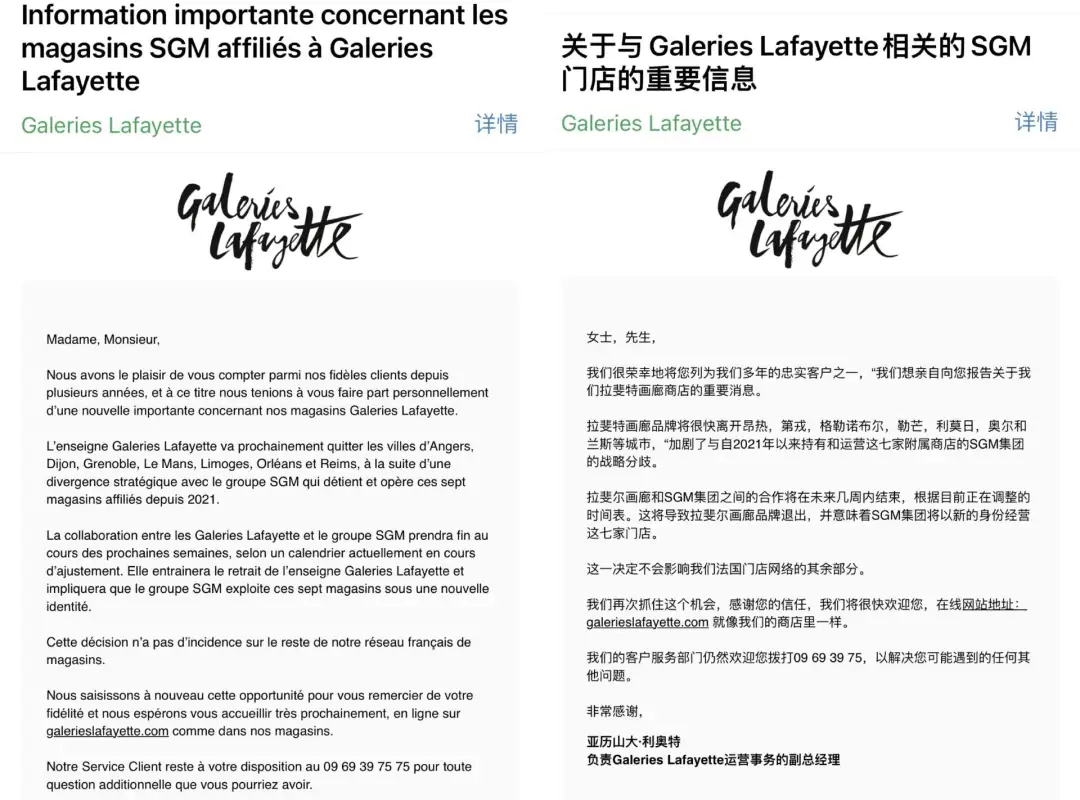

Galeries Lafayette had long expressed strong opposition, vowing to prevent Shein from entering its affiliate stores, denouncing Shein as a super-fast-fashion brand whose market positioning and business practices fundamentally conflict with Galeries Lafayette’s brand philosophy and values. On November 7, all registered members received an email announcing that, due to “strategic differences,” Galeries Lafayette would terminate its partnership with BHV’s parent company, the Société des Grands Magasins (SGM).

Source@Chris

The most formidable wave of opposition came from the French media and political sphere, whose rhetoric and actions were far more intense than the echoes from the business world.

First came regulatory interventions. In July, the French Directorate General for Competition, Consumer Affairs and Fraud Control (DGCCRF) fined Shein €40 million over misleading discounts and environmental concerns; in September, the data protection authority CNIL issued a €150 million fine for collecting consumer data without consent. This series of formal penalties set the tone for all subsequent criticism of Shein.

Next came the media. French mainstream outlets reported with clear bias: Le Monde emphasized “chaos,” “disappointment,” and “united protests,” while local papers highlighted the opening-day gap between “limited selection and high prices.” The tone across headlines was nearly unanimous—Shein was portrayed as a troublemaker.

It was the political sphere, however, that escalated the situation to a moral judgment. Anne-Cécile Violland, a lawmaker known for pushing anti-fast-fashion legislation, accused BHV of “selling its soul to a behemoth that is killing our economy,” likening Shein to “a fox in the henhouse.” In her view, BHV was complicit in destroying the French textile industry and legislation was urgently needed to stop this “unfair, massive, and aggressive competition.”

As criticisms such as “fast-fashion culprit,” “labor exploiter,” and “environmental polluter” became repeatedly invoked, new accusations emerged—“illegally selling child sexualized toys and controlled knives.” Coincidentally, around the time of Shein’s store announcement, third-party sellers on the platform were reported to have sold potentially illegal items. Although subsequent investigations suggested some doubts in the chain of responsibility, these details were largely ignored amid the rapidly spreading public outcry.

The French government then intervened comprehensively. The Minister of Economy contacted the European Commission to request a cross-border investigation, while the Interior Minister initiated a suspension procedure, stating the need to “thoroughly prevent serious threats Shein poses to public order.” On the day of the opening, the Prime Minister announced that the platform would face a “pause” procedure. All 200,000 Shein packages and 700,000 individual items arriving in France would be inspected item by item.

Although Shein immediately removed all third-party products, and Temu conducted overnight self-inspections to take down items to avoid being implicated, everyone understood that the storm was far from over

03 When Chinese Rat Race Meets French Bourgeoisie

After facing regulatory penalties, media scrutiny, and political condemnation, public opinion gradually turned its focus onto Shein itself. Its rapid rise, ultra-low-price model, and impact on traditional French culture were seen as the “original sin” of the controversy.

The most immediate reaction came from certain European groups struggling to accept the challenges posed by this new economic model. Shein’s choice to open its first global store in the heart of Paris at the long-established middle-class department store BHV was, in itself, a direct challenge to the lifestyle of the French old bourgeoisie, triggering strong cultural backlash. French society values sustainable consumption and the philosophy of “less but better,” while Shein’s “ultra-fast fashion” model—from trend discovery to shelving in just 3–7 days—creates frequent waste and pollution. This clearly conflicts with French cultural traditions that emphasize craftsmanship, creativity, and uniqueness.

As French fashion journalist Sophie Abriat noted in BoF, this model takes “disposable culture” to the extreme, using short-lived and aggressive marketing strategies to generate constantly renewed—and soon discarded—desires. Many Chinese expatriates in France have shared on Xiaohongshu that what the French oppose is not China itself, but a consumer world “reduced to price and devoid of soul,” dominated by algorithm-driven lifestyles.

Shein’s business model also draws considerable attention. The Chinese factory model represented by Shein is undoubtedly a highly efficient, massive commercial machine. Using advanced algorithms and meritocratic management, it pushes supply chains and employee productivity to the limit, while compressing prices to the lowest sustainable level in the commercial world. The externalities, however, are borne collectively by society. In the European market, this operates almost as a dimensional shock: domestic companies constrained by strict social and environmental standards struggle to compete, unregulated price wars can disrupt the market, reduce business diversity, and affect workers’ rights. “Every low price comes at a cost”—this is a structural dilemma.

Yet despite widespread criticism, Shein remains extremely popular in France. In 2023, Shein’s European revenue grew 68%, reaching €7.684 billion (approximately RMB 63 billion). It became the most visited fashion and apparel brand globally, surpassing NIKE, H&M, and ZARA. In France alone, Shein has 23 million registered users, meaning roughly one-third of the population has shopped on the platform. The reason is pragmatic: the latest authoritative statistics show that in 2023, France’s poverty rate exceeded 15% of the population, and wealth inequality reached a 30-year high. Stagnant economic growth, high inflation, and declining purchasing power force consumers to balance ideals against reality. Choosing Shein is often less about value alignment and more a rational response to economic constraints.

Moralizing fast-fashion consumers as “complicit” risks being tone-deaf and exacerbates societal divisions. Many French citizens criticize politicians on social media for “double standards,” “hypocrisy,” and “increasing the cost of living for ordinary people”—after all, France is not just about the bourgeoisie (the term is borrowed from French Bourgeois), but also renowned for its revolutionary heritage.

Consumers thus play a paradoxical role. They are both victims—forced to compromise on quality, ethics, and corporate responsibility—and accomplices, supporting through their purchases a system where price dominates, competition is relentless, efficiency reigns supreme, and local employment and industries are squeezed. Rational consumer choices made in response to immediate economic pressures collectively reinforce and intensify the very socio-economic structure that constrains them.

A lot of support voice on Tiktok,Source@Tiktok FR

Another reason Shein has become a focal point lies in the historical context of industrial transfer under globalization. In the latter half of the 20th century, Europe and the U.S. relocated low-end industries such as textiles to Asia while retaining high-value-added segments. Today’s so-called “China threat” stems from Chinese factories bypassing European capital and government intermediaries to sell directly to local consumers, challenging the existing global system. Accusations of being “environmentally unfriendly,” “exploiting labor,” or “opaque supply chains” are, to some extent, elevated as moral rhetoric, while the core driving force remains economic interest.

The French government, in this process, seeks to strengthen regulation and protect domestic industries, yet is constrained by outdated local supply chains and dependence on imports. In political and public discourse, moral slogans are deployed as commercial barriers, and Shein has become the scapegoat where these structural contradictions erupt.

04 Black Friday Eve: Paris on Trial or an Unfinished Finale

On the evening of November 7, the French administrative order to block the Shein website was temporarily suspended. Officials declared that they would “closely monitor” every move, with investigations continuing. The announcement also included a telling statement: the French government had achieved a “fundamental victory.”

While it is difficult to see the full picture of Shein’s internal decision-making, the company has never underestimated the complexity of the European regulatory and political environment. For Chinese giants navigating international controversies, government relations (GR) and public relations (PR) are critical for survival and growth. In 2024, Shein stirred considerable debate with a controversial personnel appointment: former French Interior Minister Christophe Castaner joined as an independent advisor, serving on the Regional Strategy and Corporate Social Responsibility Committee. This move was clearly strategic, provoking public outrage and triggering investigations into lobbying transparency. Reports in September indicated that Castaner had quietly stepped down. How much influence he wielded remains unclear, but it is evident that no one can stop the momentum of French regulation.

Recent reports suggest that France may accelerate a €2 per-item tariff on cross-border small parcels, potentially implemented as early as next year. Other EU member states have responded with similar proposals, including an additional €5–10 environmental tax. These measures are widely seen as specifically targeting Chinese e-commerce platforms.

However, long-term considerations are now overshadowed by immediate crises. The conflict has hit many cross-border sellers like a sudden disaster, with large numbers of product listings wiped out overnight, causing severe losses. The platforms provided no prior notice, and their subsequent responses were vague, essentially “await further instructions.”

Interestingly, perhaps to avoid panic, Shein initially explained the situation as “concerns over product listings from certain independent third-party sellers,” emphasizing that it was unrelated to the French government’s suspension procedure. Temu, in contrast, described it simply as a “technical issue.” On Xiaohongshu, countless sellers posted questions such as, “Has anyone else experienced this? Why were all my products removed?”

Sensing the crisis, Temu even took more aggressive action, delisting high-risk categories—such as toys, hardware, and gardening items—across all 32 European sites and suspending new product uploads. Compliance or not, everything was removed in a blanket approach, seemingly preferring to overreact rather than risk missing a single item.

Source: a seller posted on Xiaohongshu for help for his products got removed on Temu

ndustry insiders reveal that Shein’s French office is now in a state of “gloom and despair,” clearly unprepared for how events have unfolded. “The best-case scenario would be to abandon the Marketplace third-party platform while retaining self-operated sales,” speculated some internal employees.

A second major blow may soon arrive. Shein’s future in France will be determined by a hearing scheduled for November 26, 2025—just one day before Black Friday. Judges at the Paris Commercial Court will decide whether the company can continue operations, provided it can fully demonstrate that its products comply with French law.

Prior to the hearing, on November 19, the French Business Alliance announced an unprecedented collective lawsuit against Shein, accusing it of “unfair competition,” covering misleading advertising, non-compliant products, counterfeiting, improper data handling, and other issues, and warning that it could pose a “systemic risk” to French retail. The related hearings are expected to take place in January 2026.

The legal actions against Shein continue to escalate. This is not just a legal trial—it is a comprehensive test of culture, economy, and politics.

Yet, as Western media might ask: But, at what cost?