Author|Li Xiaotian

“This is really exciting for many people. Regardless of her individual policies or ideas, having a female leader naturally opens doors for diversity in business and other areas — and politics is one of the fields where Japan lags the most in terms of diversity,” said Rie Nishihara, chief Japan equity strategist at JPMorgan Securities Japan.

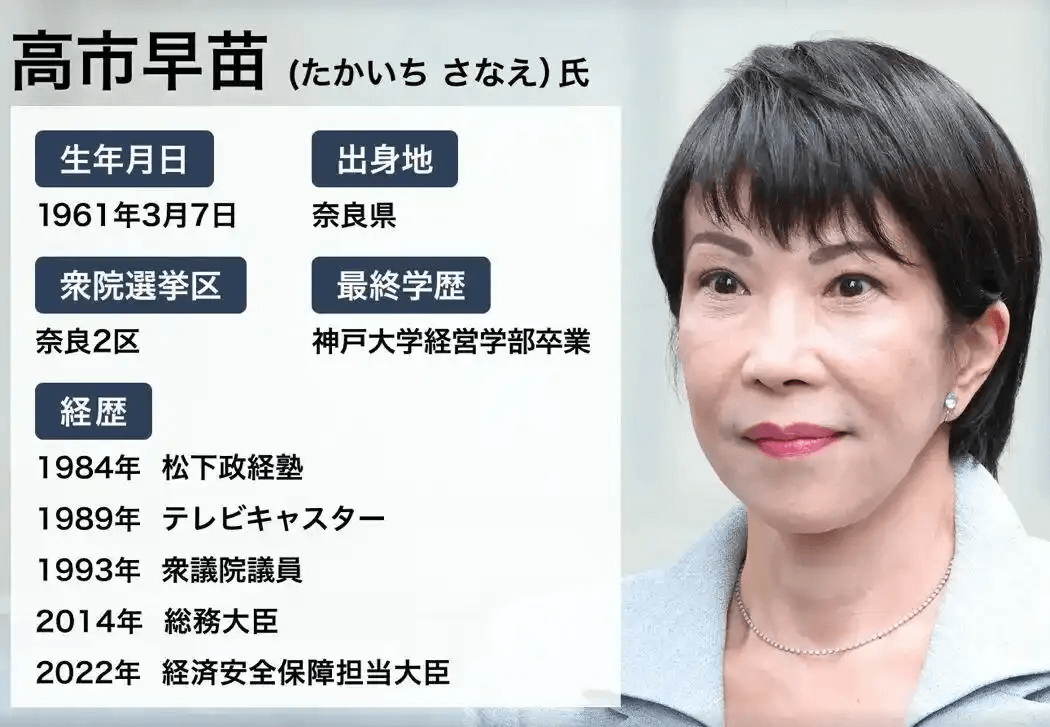

On October 21, 2025, Sanae Takaichi, the 29th president of Japan’s ruling Liberal Democratic Party, won the prime ministerial election, becoming Japan’s first female prime minister. The result is seen as a breakthrough in shattering the glass ceiling of Japanese politics. Rie Nishihara, Chief Equity Strategist at J.P. Morgan Securities Japan, expressed her excitement about the new administration. She said she looks forward not only to the government’s future policy direction but also to the subtle benefits that a female leader’s diverse perspective could bring.

Japan has long been one of the developed economies with the widest gender gap. According to the Global Gender Gap Report 2025 published by the World Economic Forum, Japan ranks 17th in gender equality among East Asia and Pacific countries, higher only than Fiji and Papua New Guinea. In The Economist’s Glass Ceiling Index, Japan ranks 27th out of 29 OECD countries. Back in 1993, when female politician Seiko Noda entered Japan’s parliament, she even had to sneak into the men’s restroom — because there were so few women in the Diet that no women’s restroom existed, and only a small section of the men’s restroom was partitioned off for female members.

But will the unprecedented rise of a female prime minister truly bring a renewal to Japan’s domestic and foreign policies? What kind of society is Sanae Takaichi inheriting? And for Chinese brands expanding into Japan,

what new opportunities and challenges will they face?

Sanae Takaichi: The Conservative Face of Japan’s First Female Prime Minister

In fact, Sanae Takaichi is a well-known right-wing conservative figure within Japan’s Liberal Democratic Party, with a strong and firm political stance. She is known for her long-term visits to the Yasukuni Shrine, advocating the revision of the pacifist constitution, renaming the Self-Defense Forces as the “National Defense Force,” and taking a tough stance toward China. On social issues, she also holds conservative views, opposing separate surnames for married couples and same-sex marriage.

Despite her pronounced personal positions, Takaichi deliberately downplayed her conservative image during the campaign to win broader electoral support. She is seen as a staunch successor to former Prime Minister Shinzo Abe’s political line. The core of her economic policy is the continuation of “Abenomics,” employing expansionary fiscal measures to stimulate economic growth. The market responded positively, pushing the Nikkei index significantly higher around the time of her election.

In foreign and security affairs, Takaichi is expected to inherit Abe’s “Free and Open Indo-Pacific” strategy, with the Japan–U.S. alliance as the cornerstone. Domestically, her personnel appointments have sparked controversy; she appointed lawmakers linked to the LDP faction “black money” scandal, drawing criticism that “factional politics is making a comeback,” which may pose challenges to her administration’s public approval ratings.

Takaichi’s assumption of office marks a new chapter in Japanese politics. How she balances inheriting Abe’s political legacy, addressing domestic economic challenges, and navigating a complex international landscape will be the central focus of her administration.

Looking at the global political arena today, female conservative leaders are not uncommon.

In 2022, Giorgia Meloni, leader of Italy’s far-right party Brothers of Italy, became prime minister. She is the first female leader of Italy since World War II and maintains a hardline immigration policy, explicitly opposes the expansion of LGBTQI+ rights, and strongly promotes a “Italy First” populist agenda. Marine Le Pen, leader of France’s far-right National Rally, openly advocates exiting the EU, opposes free trade, and promotes a “France for the French” policy, earning her the nickname “Europe’s Trump.” Alice Weidel, leader of Germany’s Alternative for Germany (AfD), similarly calls for large-scale deportations of immigrants, supports Germany leaving the eurozone and the Paris Agreement, and proposes establishing a single-market organization as an alternative, highlighting her nationalist and conservative stance.

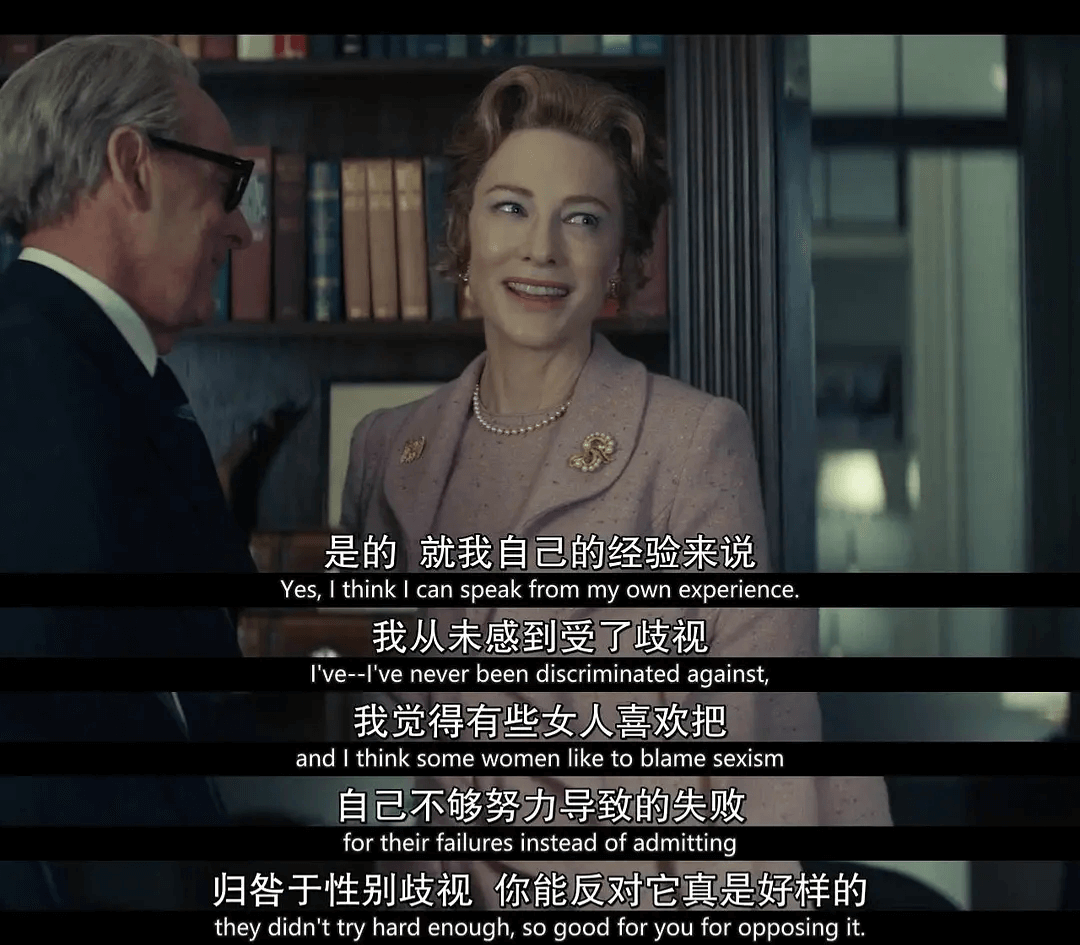

The rise of female leaders is often seen as a force for gender equality and social progress, yet politics repeatedly sees female leaders with highly conservative and rigid political views. Why is this the case?

On one hand, conservative parties promoting female leaders can be seen as a way to capitalize on the current feminist wave—a practical electoral strategy. As Mari Miura, a political science professor at Sophia University in Tokyo, noted, Takaichi’s assumption of office helps the scandal-plagued LDP refresh its image.

On the other hand, as Japanese feminist scholar Chizuko Ueno points out, some women may present themselves as “honorary men” to gain acceptance from male groups, attempting to escape the gender discrimination and oppression they face. In male-dominated political fields, adopting masculine behaviors may sometimes lead these women to be even more conservative and rigid than their male counterparts—a possible survival strategy for female leaders.

quote from<American Housewife>

Japan’s Dilemma: Economic Recovery Amid “US Dollar Panic”

As Sanae Takaichi prepares to lead Japan, what is the current state of the country’s economy and society?

First, under the ultra-loose monetary policies of the Abe administration, Japan’s economy has shown some signs of recovery after the “Lost 30 Years.” In fiscal year 2025, the average wage increase reached 5.46%, the highest level since 1991. The Japanese stock market has also performed strongly, and land prices are rising at the fastest pace since 1991.

However, real wage growth has not kept pace with the rise in prices. Living costs—including rent, utilities, and dining—are increasing, and personal consumption remains weak.

Ahead of the July upper house elections, due to rising prices and poor rice harvests, it has become common for Japanese consumers to queue for subsidized rice and carefully compare prices before making purchases.

A farm cooperative in Atami, a seaside town in southwestern Tokyo, sold out of subsidized Japanese rice within minutes of opening.

“These rice bags will only last our family a couple of weeks,” said 46-year-old Yujiro Osaki. He was one of dozens of people waiting in line to buy the subsidized rice, each 3-kilogram bag costing a few dollars less than rice of the same quality in supermarkets. “The situation in Japan right now is truly absurd.”

Meanwhile, the rapid surge in everyday consumer prices has put severe political pressure on then-Prime Minister Shigeru Ishiba. In the House of Councillors election held on July 20, the Liberal Democratic Party, since its founding in 1955, failed for the first time to secure a majority in both chambers of the National Diet. Consecutive defeats in these two chambers directly led to Ishiba stepping down.

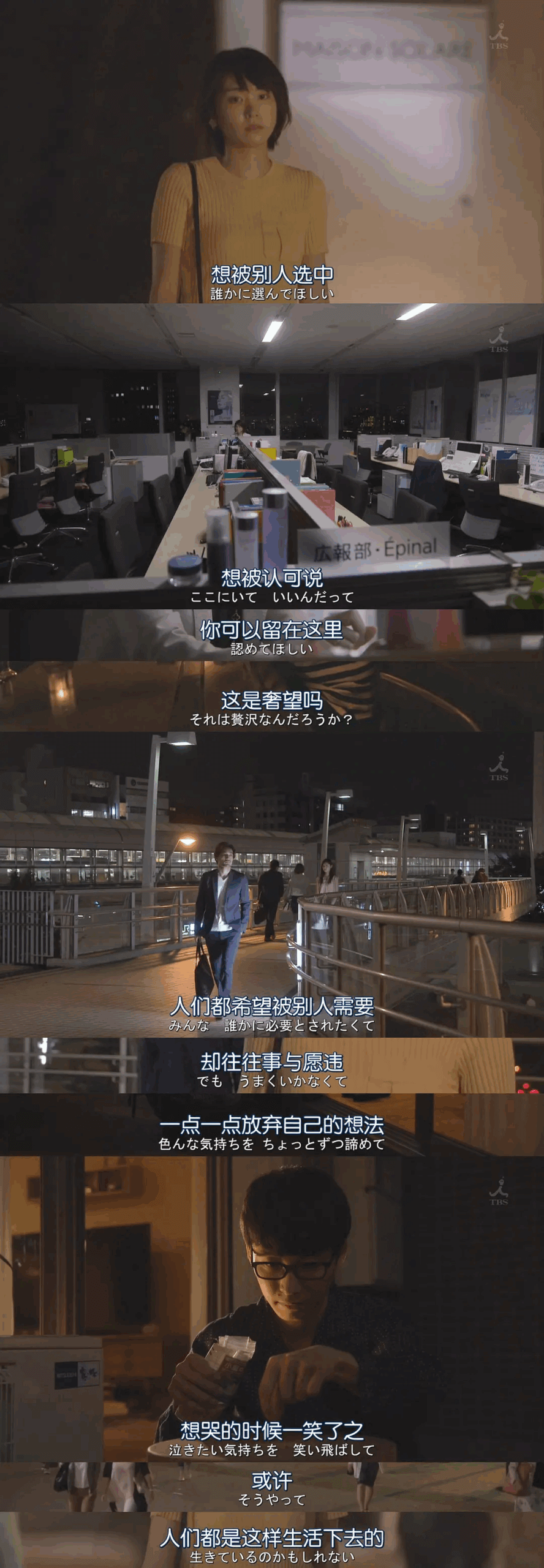

During Japan’s “rice shortage” crisis, NHK General TV aired a drama titled Eat, Sleep, and Wait for Happiness. The female protagonist, a 38-year-old single woman, had to resign from her full-time job due to a chronic illness and, unable to afford the ever-increasing rent, moved into a 45-year-old apartment complex. Her landlord was an elderly single person with no family support, and living with her was an otaku who had long withdrawn from the “normal social order.”

The three marginalized individuals of this “disconnected society” came together, carefully budgeting and selecting seasonal fruits, vegetables, and grains at the supermarket, preparing meals, and sharing daily routines and seasonal soups. They relied on and supported each other, forming close and warm human connections that allowed them to experience happiness that had long been absent.

Quote from<しあわせは食べて寝て待て / Happiness comes from eating, sleeping and waiting>

This drama is, in many ways, a true reflection of contemporary Japanese society. This highly developed capitalist country is nonetheless filled with exhausted young people fleeing the workplace and elderly individuals facing bankruptcy and solitary deaths.

According to economist Zhou Ziheng, the long-standing “lost” state of Japan stems mainly from two factors. First, demographic and consumption challenges: Japan has the most severe aging population in the world, with over 29% of the population aged 65 and above in 2024, and a shrinking workforce, directly leading to weak consumption and investment. Second, debt risks and failed economic transformation: after the 1990s, Japan’s reliance on stimulus policies created hidden debt risks, banks were slow to clean up non-performing loans, “zombie companies” were widespread, and Japan missed key opportunities during critical transitions, such as the Internet and AI revolutions, falling behind in the shift from a manufacturing powerhouse to a service-oriented economy, causing a decline in global competitiveness.

One of the consequences of aging is a shortage of labor and declining innovation. As a result, advanced modern countries have uniformly introduced immigration, which also brings latent social challenges. Japan is no exception. Low birth rates and population aging have forced Japan to rely heavily on foreign labor for economic activities, and the growth of tourism has brought large numbers of foreign visitors to core cities like Tokyo, Kyoto, and Osaka. In Japan’s homogeneous society, while outsiders provide labor- and emotion-intensive services such as construction and caregiving, they are also perceived as competing for employment and living resources, disrupting the “normal” social order.

Rising xenophobic sentiment is influencing the political landscape. In the July 2023 House of Councillors election, the right-wing populist party “Japan First” emerged, effectively mobilizing the frustration of young Japanese and reshaping the balance of political power.

Externally, after Trump returned to the White House, wielding the “tariff hammer” against the world, Japan-U.S. relations became delicate and complex. In July 2025, the two countries conducted eight rounds of negotiations and ultimately reached a large-scale trade agreement: Japanese exports to the U.S. would face a 15% tariff, lower than the 25% Trump had previously threatened, though the 50% steel and aluminum tariffs and defense spending commitments were excluded. Japan also agreed to invest $550 billion in the U.S. and to purchase $8 billion worth of U.S. agricultural products annually.

In response, Takahide Kiuchi, executive economist at Nomura Research Institute, analyzed that while the impact of a 15% tariff is less severe than Trump’s threatened 25%, the Japanese economy would still face significant setbacks; a reduction of 0.55% in real GDP would offset a full year’s actual GDP growth. Coupled with rising domestic prices, considering the effect of tariffs on GDP, he estimates there is roughly a 50% chance Japan will enter a mild recession next year.

Economic recession, declining vitality, soaring prices, unstable employment, middle-aged poverty, female impoverishment, solitary aging… a pervasive sense of malaise has spread throughout Japanese society.

Quotes from the Japanese drama <逃げるは恥だが役に立つ / We Married as a Job>

French scholar Moïsi, in his book Geopolitics of Emotion, categorizes contemporary world civilizations into three types: cultures of hope, cultures of humiliation, and cultures of fear. Based on China’s strong economic performance during the 2008 global financial crisis, the rising China falls into the category of a culture of hope, characterized by pervasive optimism about the future and a fervent enthusiasm for accelerationism. In contrast, Japan has never fully recovered from the economic crisis of the 1990s and remains entrenched in a mindset of doubt, anxiety, and fear about the future.

This mentality is also indirectly reflected in the consumption behavior of the Japanese public.

How Chinese brands leverage the “Fourth-Generation Consumption Era”

Japanese scholar Miura Ten has observed Japanese consumption patterns for over 40 years. In his book 《The Rise of Sharing: Fourth‑Stage Consumer Society in Japan》, Miura proposes that from 2005 to 2034, Japan is gradually entering a “fourth consumption society,” one that emphasizes sharing. Citizens’ consumption values are shifting from pursuing materialistic wealth and luxury to focusing more on inner spiritual richness and peace, advocating healthy consumption habits, and fostering emotional connections between people. This represents not only a change in consumption concepts but also a transformation in an entire generation’s values and lifestyle.

Regarding the reasons behind this shift in consumption values, Professor Xu Jingbo from Japan Research Center of Fudan University, told Shineglobal (霞光社)that the post-war generation in Japan, known as the “Dankai Sedai” (だんかいせだい), refers to the baby boom cohort born after World War II. This generation accumulated considerable wealth during Japan’s period of rapid economic growth and still possesses significant spending power after retirement. However, for today’s retirees, incomes have shrunk considerably, and Japanese pensions are generally low, making lavish consumption rare.

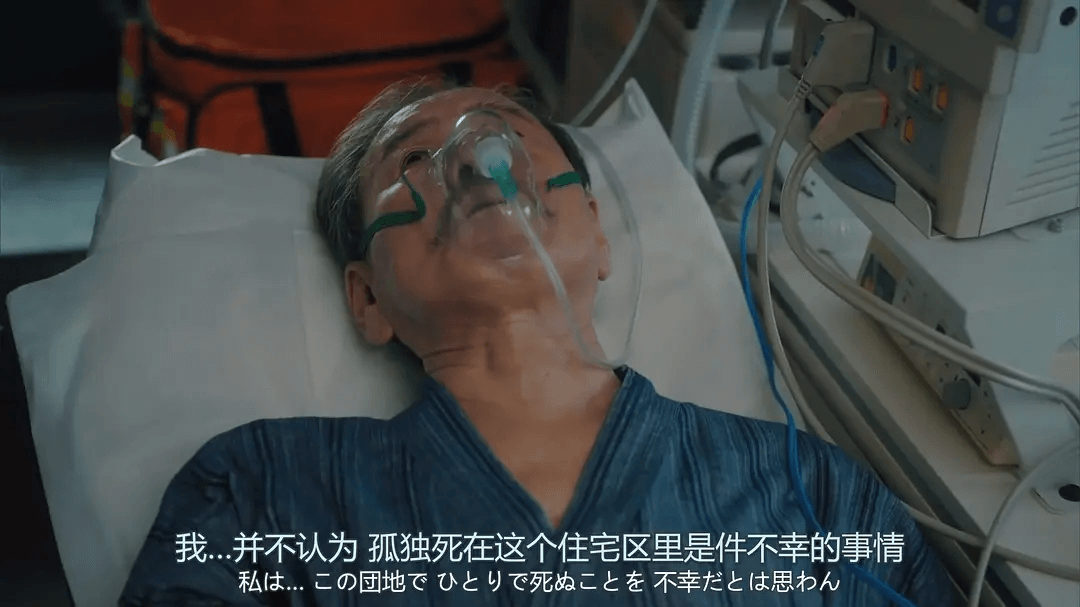

As a result, there is a substantial wealth gap within Japan’s elderly population. The 2015 Japanese nonfiction work Rōgo Hāsan (Old-Age Bankruptcy) states: “The number of elderly living alone in Japan has approached 6 million, and roughly half of them have annual incomes below the standard for public assistance. Among them, 700,000 receive public assistance. Of the rest, excluding those with sufficient savings or deposits, it is roughly estimated that over 2 million live solely on pensions, struggling to make ends meet. If they fall ill or require care, they are at risk of financial ruin…”

” I don’t think dying alone in the residential complex is necessarily misfortune “

At the same time, the main consumer force has gradually shifted to the “Heisei” and “Reiwa” generations. However, because Japan follows a seniority-based system, people under a certain age generally cannot earn high incomes in most professions. This has made this generation’s consumption more practical, with smaller portions becoming increasingly popular, and young people more willing to try experience-based consumption. Businesses and enterprises have also noticed this new trend and are developing more and more products of this type.

“It’s not that people are indifferent to materialistic desires; rather, limited income makes consumption more rational. Nowadays, Japanese people are increasingly rational in their spending. Flaunting luxury brands has become a thing of the past, and most private cars are small-displacement vehicles costing less than 2 million yen (about 100,000 RMB),” said Xu.

Taking the food and beverage industry as an example, Japan is now showing a more diverse trend, targeting high, medium, and low consumption segments. Most dining businesses are focusing on the mass market. Convenience stores such as Lawson and FamilyMart have developed dozens of types of bento boxes, priced around 500-800 yen (3.25-5.2 USD). The reason behind this is that since the collapse of the bubble economy in the 1990s, most people’s incomes have stopped growing or even slightly declined, making previous high-consumption habits unsustainable.

Meanwhile, high-end restaurants (ryotei) that emphasize premium ingredients and service still exist, though their numbers have slightly decreased. In the 1980s bubble economy, executives of major and medium-sized companies spent significant sums on entertainment and client reception. Today, such spending has sharply declined, negatively impacting ryotei businesses. Many of these restaurants now cater mainly to mid-to-high-end foreign tourists. Ordinary diners and family restaurants, which were once widespread, have seen moderate growth compared to the past.

A Japanese social e-commerce startup, Kauche, conducted a survey of 1,053 users nationwide at the end of September regarding rising prices. Almost all respondents (over 99%) said that price increases were a burden. The products most affected by price increases were rice and vegetables. Families cut spending the most on food and dining out, accounting for 47% of the reduction.

Under the macro trend of consumption downgrading, Chinese brands entering the Japanese market need to adapt to new consumer trends and make localized adjustments accordingly.

In response, Xu recommends that Chinese brands should first develop innovative styles that appeal to japanese young consumers; second, while creating emotional value, do not neglect practical functionality; and third, set reasonable pricing.

In the food and beverage sector, Xu observes that the Chinese brand Yang Guo Fu Malatang has become extremely popular in Japan, setting new trends. “This is because the flavor of malatang is unique to Japan, offering novelty for young consumers; secondly, the ingredients can be freely selected by customers, providing a distinctive, experiential dining experience; thirdly, Yang Guo Fu has adapted its flavors to suit the Japanese market, making it more appealing, while maintaining a relatively clean dining environment and reasonable prices. As a result, it has opened many chain stores in Japan, most of which are packed, with customers often waiting in line for over half an hour.”

Yang Guo Fu Malatang store in Shibuya, Japan

Chinese international student Jason also shared that lining up for Yang Guo Fu Malatang has become a trendy activity for many young people in Japan. “Many Japanese youths who are enthusiastic about malatang say that the unique DIY ingredient selection provides them with a special experience.”

At the same time, Xu added that, overall, Chinese brands in Japan still lack a sense of premium quality and high added value. The global success of Japanese washoku (traditional cuisine) overseas, however, could offer valuable lessons and inspiration for Chinese brands.

When Japan applied for washoku to be recognized as a UNESCO World Heritage, it put forward four key principles:

- Respect for diverse, fresh ingredients and their inherent flavors (多様で新鮮な食材とその持ち味の尊重)

- Nutritional balance supporting a healthy diet (健康的な食生活を支える栄養バランス)

- Expression of the beauty of nature and seasonal changes (自然の美しさや季節の移ろいの表現)

- Close connection with annual events such as New Year celebrations (正月などの年中行事との密接な関わり)

“These principles are easily accepted and appreciated by mainstream countries around the world. The Japanese did not overly emphasize ‘Japan’ itself, but skillfully combined unique Japanese culture, aesthetics, and universal values. This approach led to a successful application and is worth learning from.”

The rising popularity of the Chinese beauty brand Florasis (Hua Xi Zi) in Japan also stems from the combination of ethnic characteristics and universal aesthetics.

In 2020, Florasis’ limited edition series featuring Miao silverware appeared on a large screen in Shibuya, Tokyo’s trendy district. Prior to that, Japan had already experienced a surge in “Chinese-style makeup” (中国风メイク), with bold and vivid Chinese makeup styles capturing the attention of Japanese consumers. U.S. media outlet Business Wire commented: “Looking at Florasis’ past cosmetic products, it is evident that the brand has consistently aimed to promote Chinese culture. Its products replicate traditional Chinese craftsmanship, showcasing exquisite cosmetic and manufacturing skills. Florasis is redefining the standard for Chinese cosmetics, continuously updating Japanese consumers’ perception of Chinese beauty. In today’s era of aesthetic diversity, ethnic beauty is undeniably captivating.”

In the early 21st century, Japanese business and technology circles began using the term “ガラパゴス化” (garapagosu-ka), or the “Galápagos effect,” to describe how Japan’s business sector had become insular and resistant to change. Much like the Galápagos Islands in the eastern Pacific, which evolved in isolation to develop unique yet fragile forms of life, Japan’s industries had developed their own distinctive, self-contained ecosystem.

Today, Japan seems to be an extreme microcosm of a world that is simultaneously aging and impoverished. It is difficult to judge whether a country is keeping pace solely from an evolutionary perspective, because aging is a global issue. Today’s young people will live in the aging world of tomorrow, and regardless of the result, preparation is always essential.

What we can learn from the Japanese market is how to age with calmness and equanimity.